Sophie Scholl: Remembering the White Rose activist on what would have been her 100th birthday

Sophie Scholl, one of the key figures of the Weiße Rose (White Rose) group, would have celebrated her one hundredth birthday on Sunday. Here we take a look at the impact she made at such a young age and the impression she has left on the German history books.

Scholl is regarded by many Germans as an almost saint-like figure and it is likely that you will have seen countless schools, streets and prizes bearing her name across the country.

Sophie is seen by many as a symbol of unwavering resistance and immense courage, her principles never faltering in her fight for resistance.

The White Rose was a group of students at the University of Munich who encouraged opposition to the National Socialists during the Second World War. The young activists anonymously spread information leaflets around the university and the wider city between 1942 and 1943, before the central figures were discovered and arrested by the Gestapo.

Though the White Rose was a small endeavour led by a handful of students, it has left an indelible mark on German history.

Sophie, along with her brother Hans, was one of the core members of the group.

READ ALSO: What we can learn from the White Rose siblings

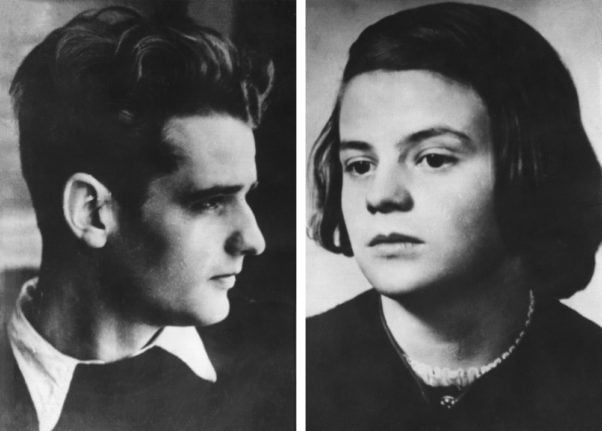

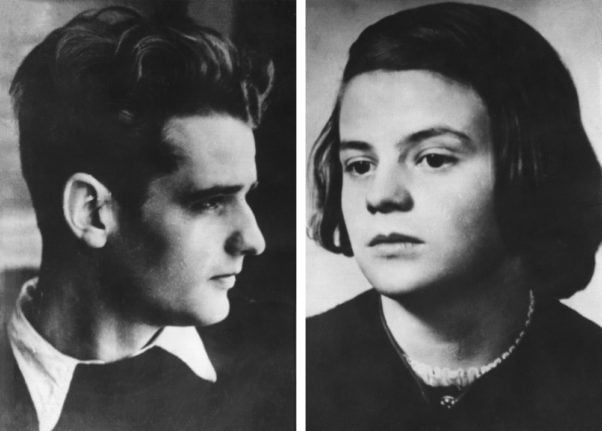

Hans and Sophie Scholl. Photo: DPA

Political beginnings

Sophie Scholl was born in May 1921 in Forchtenberg, a small town in Baden-Wurttemberg, and her family moved to Ulm when she was ten. Although their father was a liberal politician and ardent Nazi critic, both Sophie and her brother were part of the Hitler Youth program.

Sophie was drawn in by the Nazi party’s cult of the youth and found herself intrigued by the National Socialists’ focus on nature and community. She quickly rose within the ranks of the Bund Deutscher Mädel (League of German Girls), the female branch of the party’s youth group.

Although they were initially enthusiastic, Hans and Sophie’s relationship with the nationalist party and its political methods quickly soured.

As she grew older, Sophie realised the ideology of the National Socialists was not in line with her strong moral convictions. This realisation was particularly enabled by her parents’ openness about their disdain for Hitler’s party, and their willingness to talk freely about political matters with their children.

Sophie was quick to immerse herself in resistance activism when she started studying in Munich, where she joined the Weiße Rose.

The White Rose

The White Rose was a non-violent resistance group led by students at the University of Munich. The group became active on June 17th 1942 when they published and distributed their first pamphlet urging readers to oppose the Nazi regime.

The core members of the group were Sophie’s brother Hans Scholl, Alexander Schmorell, Willi Graf, Christoph Probst, and Kurt Huber. Together, they launched an information and graffiti campaign in Munich against the National Socialists.

Sophie studied Biology and Philosophy and quickly fell in with her brother’s friendship group, who became known for their alternative political views. Sophie only involved herself in the White Rose after two information pamphlets had been distributed, and it was only then she learned of her brother’s involvement in the movement.

Sophie was seen as a particularly valuable member of the group because, being a woman, she was less likely to be stopped and questioned by the SS - the paramilitary force of the Nazi party.

Once Sophie joined the writing team, three more leaflets were distributed by the student group across the summer of 1942.

Sophie’s religious and philosophical convictions began to drive the approach of the White Rose, whose pamphlets focused on the Biblical and intellectual arguments for resistance, encouraging readers to passively resist the National Socialist regime.

On February 18, 1943, the Scholl siblings scattered hundreds of anti-Nazi pamphlets into the atrium of the University of Munich. This was a daring act of public protest which ultimately cost the Scholl siblings their lives.

Bavarian State Premier Markus Söder (CSU) places flowers at a memorial for Sophie Scholl at the University of Munich (Ludwig Maximilians University) on Friday. Photo: picture alliance/dpa/dpa Pool | Peter Kneffel

Arrest and trial

Sophie Scholl, along with the other members of the activist group, were arrested following the public act, which was observed by a member of the university’s maintenance team. This led the Gestapo to take the students into custody and later to try them in public show trials.

The main Gestapo interrogator initially assumed Sophie to be innocent, as she had no incriminating evidence on her person when she was arrested. However, in an attempt to protect other members of the group, she tried to claim full responsibility for the spreading of anti-Nazi documents.

Within their show trials, the defendants had no opportunity to provide testimonies, but Sophie famously interrupted the judge multiple times throughout the trial.

In the people’s court, she is reported to have said before the judge “Somebody, after all, had to make a start. What we wrote and said is also believed by many others. They just don't dare express themselves as we did”.

Execution and legacy

On February 22nd 1943, Sophie, her brother Hans, and their friend Christoph Probst were found guilty of treason and sentenced to death. They were executed by guillotine just a few hours later.

Her last words, as she walked towards her execution, came “such a fine, sunny day, and I have to go... What does my death matter, if through us, thousands of people are awakened and stirred to action?”

It seems that, even in her final moments, Sophie recognised the impact of her courage in the face of National Socialism. Despite losing her life at such a young age, Scholl lives on in German history as a symbol of powerful defiance, her legacy one of resistance and righteousness.

Scholl has been commemorated across Germany in art, media and education. In 2003, a bust of Sophie Scholl was installed in the Walhalla temple in Bavaria and she was named as one of the most influential Germans of all time in ZDF’s Unsere Besten (our best) campaign.

Sophie was also the subject of a major film entitled Sophie Scholl – Die letzten Tage (Sophie Scholl – The Final Days).

Comments

See Also

Scholl is regarded by many Germans as an almost saint-like figure and it is likely that you will have seen countless schools, streets and prizes bearing her name across the country.

Sophie is seen by many as a symbol of unwavering resistance and immense courage, her principles never faltering in her fight for resistance.

The White Rose was a group of students at the University of Munich who encouraged opposition to the National Socialists during the Second World War. The young activists anonymously spread information leaflets around the university and the wider city between 1942 and 1943, before the central figures were discovered and arrested by the Gestapo.

Though the White Rose was a small endeavour led by a handful of students, it has left an indelible mark on German history.

Sophie, along with her brother Hans, was one of the core members of the group.

READ ALSO: What we can learn from the White Rose siblings

Hans and Sophie Scholl. Photo: DPA

Political beginnings

Sophie Scholl was born in May 1921 in Forchtenberg, a small town in Baden-Wurttemberg, and her family moved to Ulm when she was ten. Although their father was a liberal politician and ardent Nazi critic, both Sophie and her brother were part of the Hitler Youth program.

Sophie was drawn in by the Nazi party’s cult of the youth and found herself intrigued by the National Socialists’ focus on nature and community. She quickly rose within the ranks of the Bund Deutscher Mädel (League of German Girls), the female branch of the party’s youth group.

Although they were initially enthusiastic, Hans and Sophie’s relationship with the nationalist party and its political methods quickly soured.

As she grew older, Sophie realised the ideology of the National Socialists was not in line with her strong moral convictions. This realisation was particularly enabled by her parents’ openness about their disdain for Hitler’s party, and their willingness to talk freely about political matters with their children.

Sophie was quick to immerse herself in resistance activism when she started studying in Munich, where she joined the Weiße Rose.

The White Rose

The White Rose was a non-violent resistance group led by students at the University of Munich. The group became active on June 17th 1942 when they published and distributed their first pamphlet urging readers to oppose the Nazi regime.

The core members of the group were Sophie’s brother Hans Scholl, Alexander Schmorell, Willi Graf, Christoph Probst, and Kurt Huber. Together, they launched an information and graffiti campaign in Munich against the National Socialists.

Sophie studied Biology and Philosophy and quickly fell in with her brother’s friendship group, who became known for their alternative political views. Sophie only involved herself in the White Rose after two information pamphlets had been distributed, and it was only then she learned of her brother’s involvement in the movement.

Sophie was seen as a particularly valuable member of the group because, being a woman, she was less likely to be stopped and questioned by the SS - the paramilitary force of the Nazi party.

Once Sophie joined the writing team, three more leaflets were distributed by the student group across the summer of 1942.

Sophie’s religious and philosophical convictions began to drive the approach of the White Rose, whose pamphlets focused on the Biblical and intellectual arguments for resistance, encouraging readers to passively resist the National Socialist regime.

On February 18, 1943, the Scholl siblings scattered hundreds of anti-Nazi pamphlets into the atrium of the University of Munich. This was a daring act of public protest which ultimately cost the Scholl siblings their lives.

Bavarian State Premier Markus Söder (CSU) places flowers at a memorial for Sophie Scholl at the University of Munich (Ludwig Maximilians University) on Friday. Photo: picture alliance/dpa/dpa Pool | Peter Kneffel

Arrest and trial

Sophie Scholl, along with the other members of the activist group, were arrested following the public act, which was observed by a member of the university’s maintenance team. This led the Gestapo to take the students into custody and later to try them in public show trials.

The main Gestapo interrogator initially assumed Sophie to be innocent, as she had no incriminating evidence on her person when she was arrested. However, in an attempt to protect other members of the group, she tried to claim full responsibility for the spreading of anti-Nazi documents.

Within their show trials, the defendants had no opportunity to provide testimonies, but Sophie famously interrupted the judge multiple times throughout the trial.

In the people’s court, she is reported to have said before the judge “Somebody, after all, had to make a start. What we wrote and said is also believed by many others. They just don't dare express themselves as we did”.

Execution and legacy

On February 22nd 1943, Sophie, her brother Hans, and their friend Christoph Probst were found guilty of treason and sentenced to death. They were executed by guillotine just a few hours later.

Her last words, as she walked towards her execution, came “such a fine, sunny day, and I have to go... What does my death matter, if through us, thousands of people are awakened and stirred to action?”

It seems that, even in her final moments, Sophie recognised the impact of her courage in the face of National Socialism. Despite losing her life at such a young age, Scholl lives on in German history as a symbol of powerful defiance, her legacy one of resistance and righteousness.

Scholl has been commemorated across Germany in art, media and education. In 2003, a bust of Sophie Scholl was installed in the Walhalla temple in Bavaria and she was named as one of the most influential Germans of all time in ZDF’s Unsere Besten (our best) campaign.

Sophie was also the subject of a major film entitled Sophie Scholl – Die letzten Tage (Sophie Scholl – The Final Days).

Join the conversation in our comments section below. Share your own views and experience and if you have a question or suggestion for our journalists then email us at [email protected].

Please keep comments civil, constructive and on topic – and make sure to read our terms of use before getting involved.

Please log in here to leave a comment.