The Israeli intellectuals making Berlin more Hebrew than ever before

The Holocaust largely ended Jewish cultural life in Germany. But as ever more Israelis move to Berlin, a growing cultural movement is helping create a new Jewish diaspora with a distinctly Hebrew edge.

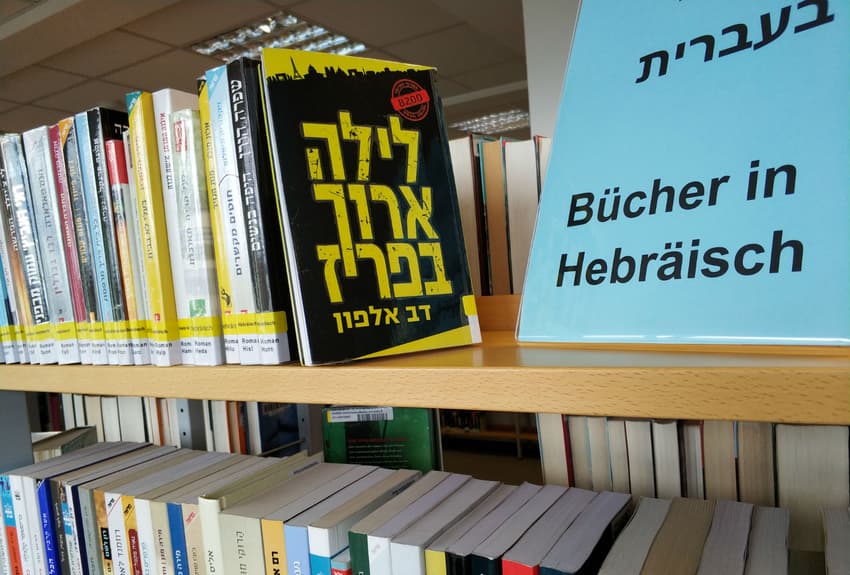

Antje Haußner, the director of the Betinna-von-Arnim library in Prenzlauer Berg, Berlin, turns the book in her hand over and over again, puzzled. She is trying to add it to the public libraries' catalogue, but the book is in Hebrew, a challenge even for the most determined German librarian.

"This is surely exhausting," she says, inspecting the pile of books on the shelf in front of her. "But it's brilliant. It is really fantastic what we've accomplished here!"

Last month, the first Hebrew books entered Berlin's public libraries, introducing the label "Hebräisch" into the German institution for the first time. Behind the initiative is a group of Israeli Berliners. They have joined a remarkable number of projects in the field of language and literature, all making Berlin more Hebrew than ever before.

Bringing Hebrew to Berlin is not only charged with historical symbolism. It also touches on baffling questions of identity. The cultural entrepreneurs who promote it go against the grain of conventional divisions, according to which Hebrew belongs to Israel and outside of it is only a diaspora of Jewish communities.

Compelled by their passion for their language, they dare to imagine something new.

'Judaism for me is Hebrew'

Itay Novik, who founded the group "Hebrew Public Library," stands excitedly in front of the new bookshelf.

"This makes me feel I've done something that makes this city a little bit more home for everybody," he says. "It's a general service for Berlin."

In the last three years Novik's group has collected donations of more than 500 books, now slowly finding their place on the new shelf. Eventually they will revolutionize the small library's collection, which next to 45,000 German items contains no more than 640 English books, 100 in French, and 35 in Spanish.

.jpg) "Beraleh" - a Hebrew newspaper for Berlin's children.

"Beraleh" - a Hebrew newspaper for Berlin's children.

"It is meaningful that it's the first time Hebrew books can be borrowed in Berlin's public libraries," Novik says. "But also that it's normal. We're not in the ghetto, we won't go to the library of the Jewish community, where there's a police barrier and security checks at the entrance. We're not part of this community, and we don't need this zoo-like experience with cages everywhere. We'll go to the public library, like any other person who lives in this city."

Novik's mother was born in a Displaced Persons camp near Kassel, Germany, to two stateless Holocaust survivors whose entire families had perished. But this background is hardly relevant to his everyday life in Berlin, where he's been living for seven years. "I am very secular in this sense. I don't live here as the representative of my family who came to Germany 'to show them', and I don't walk in the streets and think 'here Jews hid during the Holocaust'. It doesn't work like this."

For Tal Alon, the founder of "Spitz", the first Hebrew magazine in Berlin, the symbolic meaning of Novik's project is moving. "The trivial references to the Holocaust that Israelis see everywhere when they first come to Berlin don't impress me anymore, but this is something else," she says. "Now we have the empty library at Bebelplatz [the memorial to the Nazi book-burning] and Hebrew books in the public library."

Alon's magazine is now an established institution in the Berlin-Israeli community. When it first appeared in 2012 its subtitle read 'Israelis@Berlin', but later it changed to 'a Berlin Hebrew magazine'.

Tal Alon. Photo: Olaf Kühnemann

Tal Alon. Photo: Olaf Kühnemann

"I soon realized it was incorrect branding," Alon says. "I felt Israel wasn't the core of this project, but the Hebrew. This also had to do with my personal journey of exploring my identity. As a secular and atheist Jew, I soon realized that Judaism for me is largely Hebrew. This is the part I'm emotionally and authentically connected with, and this is what I want to pass down to my children. My Jewish identity is, ultimately, my Hebrew identity."

Alon moved to Berlin from Tel Aviv in 2009 with her partner and two children, leaving behind a successful journalistic career. "'Spitz' was a project of finding my place in Berlin," she says. "It has a huge part in my connection to this place and in the very fact I stayed here."

What kind of future Hebrew has in Berlin, Alon cannot say. "This is the million-dollar-question. In terms of my identity, I'm setting my sights on the language. And I don't know if it's sustainable. Maybe because of this question I still feel temporary here. It's not that I want my children to be Israelis, but it does scare me that the distance will make Hebrew an esoteric part of their lives."

Both Novik and Alon cite Tal Hever-Chybowski as an important source of influence on their thought. In 2016 Hever-Chybowski founded "Mikan ve'eylakh: Journal for diasporic Hebrew", dedicated to "the existence of Hebrew as a world language, scattered across space and time," as explained on its website. It pays tribute to past golden ages of Hebrew Berlin, like at the end of the eighteenth century, when Hebrew journals were published here by local Jewish intellectuals.

"Mikan ve'eylakh" offers a radical and thought-provoking programme, as it consciously turns its back on Israel. It wishes to revive a pre-Zionist Hebrew and offer a space for a non-Zionist one. Inspired by the Yiddish language, Hever-Chybowski dreams of a Hebrew "devoid of state, military, police and bureaucracy."

"It was born in Berlin out of a feeling of loneliness within the Hebrew," said Hever-Chybowski in an interview to Alon's magazine "Spitz" in 2016. "I felt that the Hebrew I consume tells me that it's somewhere else, not in my place."

"Ideologically, I can identify with this message," says Alon today. "It is an important voice in the community. But emotionally I don't really identify with it. My Hebrew is still rooted in Israel."

'It helps me feel at home'

Two weeks after the launch of the first public Hebrew bookshelf, a small crowd gathers for a poetry evening in a small theatre hall in Berlin's Mitte district. The guest is a visiting Israeli poet. She reads from her new book and answers questions from an engaged audience.

The bare, black-painted walls of the hall create a strange atmosphere of spacelessness. As the discussion deepens, one can easily forget that outside is a chilly Berlin spring evening and not the humid and chaotic streets of southern Tel Aviv.

The organizer of the event is Michal Zamir, who runs a monthly literary salon in her house. About 40 people come to these meetings to exchange books, have coffee and cake, and read from their own writings.

"Young people, families, older people who followed love to Berlin and now miss the Hebrew, or people who simply feel lonely," Zamir explains. "Also Germans who learn Hebrew or are interested in Hebrew literature pass by."

.jpg) Michal Zamir. Photo: Lukas Mühlethaler

Michal Zamir. Photo: Lukas Mühlethaler

Israeli writers and poets who visit Berlin often contact Zamir, and she organizes events like this one.

Another Israeli poet who contacted Zamir is Gal Mashiach, who moved to Berlin one and a half years ago. Here he discovered how important the mere visual presence of Hebrew around him can be.

"When I suddenly see a letter on the street, my mind clings to it," he says.

This understanding led him to establish "Beraleh", a Hebrew newspaper for Berlin's children, whose first issue is due next month.

"'Beraleh' is meant for children who wish to preserve something of the language, an emotion, a childhood memory," he says. "It was born out of longing for the Hebrew letter. And it's something I need at home, too, between all these Latin letters everywhere."

"These projects, like the Hebrew Public Library, help me somehow," Mashiach adds. "They relax me. They make me feel more at home."

At the end of the poetry evening, the moderator turns to thank the audience. "We've debated a lot whether to run this event tonight," he says. "As you know, today is Holocaust Memorial Day in Israel, and we weren't sure this is appropriate. But I'm happy we did it."

"Our victory is organizing a Hebrew event here. And we cannot always do everything according to the Israeli calendar."

Comments

See Also

Antje Haußner, the director of the Betinna-von-Arnim library in Prenzlauer Berg, Berlin, turns the book in her hand over and over again, puzzled. She is trying to add it to the public libraries' catalogue, but the book is in Hebrew, a challenge even for the most determined German librarian.

"This is surely exhausting," she says, inspecting the pile of books on the shelf in front of her. "But it's brilliant. It is really fantastic what we've accomplished here!"

Last month, the first Hebrew books entered Berlin's public libraries, introducing the label "Hebräisch" into the German institution for the first time. Behind the initiative is a group of Israeli Berliners. They have joined a remarkable number of projects in the field of language and literature, all making Berlin more Hebrew than ever before.

Bringing Hebrew to Berlin is not only charged with historical symbolism. It also touches on baffling questions of identity. The cultural entrepreneurs who promote it go against the grain of conventional divisions, according to which Hebrew belongs to Israel and outside of it is only a diaspora of Jewish communities.

Compelled by their passion for their language, they dare to imagine something new.

'Judaism for me is Hebrew'

Itay Novik, who founded the group "Hebrew Public Library," stands excitedly in front of the new bookshelf.

"This makes me feel I've done something that makes this city a little bit more home for everybody," he says. "It's a general service for Berlin."

In the last three years Novik's group has collected donations of more than 500 books, now slowly finding their place on the new shelf. Eventually they will revolutionize the small library's collection, which next to 45,000 German items contains no more than 640 English books, 100 in French, and 35 in Spanish.

.jpg) "Beraleh" - a Hebrew newspaper for Berlin's children.

"Beraleh" - a Hebrew newspaper for Berlin's children.

"It is meaningful that it's the first time Hebrew books can be borrowed in Berlin's public libraries," Novik says. "But also that it's normal. We're not in the ghetto, we won't go to the library of the Jewish community, where there's a police barrier and security checks at the entrance. We're not part of this community, and we don't need this zoo-like experience with cages everywhere. We'll go to the public library, like any other person who lives in this city."

Novik's mother was born in a Displaced Persons camp near Kassel, Germany, to two stateless Holocaust survivors whose entire families had perished. But this background is hardly relevant to his everyday life in Berlin, where he's been living for seven years. "I am very secular in this sense. I don't live here as the representative of my family who came to Germany 'to show them', and I don't walk in the streets and think 'here Jews hid during the Holocaust'. It doesn't work like this."

For Tal Alon, the founder of "Spitz", the first Hebrew magazine in Berlin, the symbolic meaning of Novik's project is moving. "The trivial references to the Holocaust that Israelis see everywhere when they first come to Berlin don't impress me anymore, but this is something else," she says. "Now we have the empty library at Bebelplatz [the memorial to the Nazi book-burning] and Hebrew books in the public library."

Alon's magazine is now an established institution in the Berlin-Israeli community. When it first appeared in 2012 its subtitle read 'Israelis@Berlin', but later it changed to 'a Berlin Hebrew magazine'.

Tal Alon. Photo: Olaf Kühnemann

"I soon realized it was incorrect branding," Alon says. "I felt Israel wasn't the core of this project, but the Hebrew. This also had to do with my personal journey of exploring my identity. As a secular and atheist Jew, I soon realized that Judaism for me is largely Hebrew. This is the part I'm emotionally and authentically connected with, and this is what I want to pass down to my children. My Jewish identity is, ultimately, my Hebrew identity."

Alon moved to Berlin from Tel Aviv in 2009 with her partner and two children, leaving behind a successful journalistic career. "'Spitz' was a project of finding my place in Berlin," she says. "It has a huge part in my connection to this place and in the very fact I stayed here."

What kind of future Hebrew has in Berlin, Alon cannot say. "This is the million-dollar-question. In terms of my identity, I'm setting my sights on the language. And I don't know if it's sustainable. Maybe because of this question I still feel temporary here. It's not that I want my children to be Israelis, but it does scare me that the distance will make Hebrew an esoteric part of their lives."

Both Novik and Alon cite Tal Hever-Chybowski as an important source of influence on their thought. In 2016 Hever-Chybowski founded "Mikan ve'eylakh: Journal for diasporic Hebrew", dedicated to "the existence of Hebrew as a world language, scattered across space and time," as explained on its website. It pays tribute to past golden ages of Hebrew Berlin, like at the end of the eighteenth century, when Hebrew journals were published here by local Jewish intellectuals.

"Mikan ve'eylakh" offers a radical and thought-provoking programme, as it consciously turns its back on Israel. It wishes to revive a pre-Zionist Hebrew and offer a space for a non-Zionist one. Inspired by the Yiddish language, Hever-Chybowski dreams of a Hebrew "devoid of state, military, police and bureaucracy."

"It was born in Berlin out of a feeling of loneliness within the Hebrew," said Hever-Chybowski in an interview to Alon's magazine "Spitz" in 2016. "I felt that the Hebrew I consume tells me that it's somewhere else, not in my place."

"Ideologically, I can identify with this message," says Alon today. "It is an important voice in the community. But emotionally I don't really identify with it. My Hebrew is still rooted in Israel."

'It helps me feel at home'

Two weeks after the launch of the first public Hebrew bookshelf, a small crowd gathers for a poetry evening in a small theatre hall in Berlin's Mitte district. The guest is a visiting Israeli poet. She reads from her new book and answers questions from an engaged audience.

The bare, black-painted walls of the hall create a strange atmosphere of spacelessness. As the discussion deepens, one can easily forget that outside is a chilly Berlin spring evening and not the humid and chaotic streets of southern Tel Aviv.

The organizer of the event is Michal Zamir, who runs a monthly literary salon in her house. About 40 people come to these meetings to exchange books, have coffee and cake, and read from their own writings.

"Young people, families, older people who followed love to Berlin and now miss the Hebrew, or people who simply feel lonely," Zamir explains. "Also Germans who learn Hebrew or are interested in Hebrew literature pass by."

.jpg) Michal Zamir. Photo: Lukas Mühlethaler

Michal Zamir. Photo: Lukas Mühlethaler

Israeli writers and poets who visit Berlin often contact Zamir, and she organizes events like this one.

Another Israeli poet who contacted Zamir is Gal Mashiach, who moved to Berlin one and a half years ago. Here he discovered how important the mere visual presence of Hebrew around him can be.

"When I suddenly see a letter on the street, my mind clings to it," he says.

This understanding led him to establish "Beraleh", a Hebrew newspaper for Berlin's children, whose first issue is due next month.

"'Beraleh' is meant for children who wish to preserve something of the language, an emotion, a childhood memory," he says. "It was born out of longing for the Hebrew letter. And it's something I need at home, too, between all these Latin letters everywhere."

"These projects, like the Hebrew Public Library, help me somehow," Mashiach adds. "They relax me. They make me feel more at home."

At the end of the poetry evening, the moderator turns to thank the audience. "We've debated a lot whether to run this event tonight," he says. "As you know, today is Holocaust Memorial Day in Israel, and we weren't sure this is appropriate. But I'm happy we did it."

"Our victory is organizing a Hebrew event here. And we cannot always do everything according to the Israeli calendar."

Join the conversation in our comments section below. Share your own views and experience and if you have a question or suggestion for our journalists then email us at [email protected].

Please keep comments civil, constructive and on topic – and make sure to read our terms of use before getting involved.

Please log in here to leave a comment.