Last week a brief series of events played out that are all-too-familiar if you live in Germany.

A journalist published a photo of a man in the suburbs of Berlin with a large tattoo of the Auschwitz concentration camp across his lower back, leading to much hue and cry on news sites and social networks.

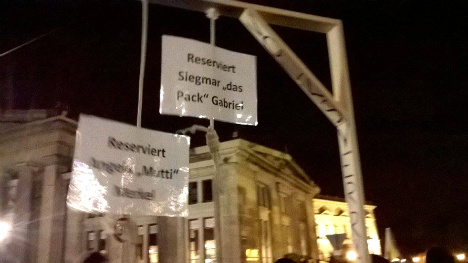

The response was typical of such cases – such as the recent Pegida demonstration where a marcher brought a miniature gallows bearing the names of Chancellor Angela Merkel and Vice-Chancellor Sigmar Gabriel.

A mock gallows bearing the names of Chancellor Angela Merkel and Vice-Chancellor Sigmar Gabriel at an October Pegida rally. Photo: DPA

Then as now, the loudest calls were for police and prosecutors to investigate the person behind the objectionable speech as a criminal case.

These were knee-jerk reactions typical of how the political mainstream – and the left – in Germany have allowed themselves to grow lazy.

By relying on the police and the judiciary to do the hard work of defining the limits of acceptable discourse for them, they've failed to connect with the people vulnerable to far-right thinking with a positive vision of a society that upholds modern European values.

In the USA, with its strong free-speech protections, politicians and activists have to argue back at their opponents, calling out their words as factually wrong or morally unacceptable.

That's just what large numbers of people did last week, for example, when Donald Trump tweeted crime statistics that had been manipulated by neo-Nazis to claim that black people were responsible for 81 percent of murders against white people (the real number is 14 percent).

In Germany, meanwhile, such utterances provoke a wave of cookie-cutter condemnations from the political mainstream and calls for police investigations – usually under the law against Volksverhetzung (incitement of the people) or the law against membership or using the symbols of banned organizations such as the Nazi party.

But the law is a blunt instrument for policing speech, and it's often used to smash the most visible offenders only to leave crumbs of resentment lurking in the cracks in society.

That's painfully visible in the recent movie Er Ist Wieder Da (Look Who's Back), based on the book of the same name which imagines Hitler awakening in the Berlin of 2011.

In costume as the Führer, actor Oliver Masucci visited pubs, restaurants, bratwurst stands and a "neo-Nazi vegan cooking show" across Germany – and found widespread resentment of the fact that people aren't free to speak their mind.

A poster showing actor Oliver Masucci playing Hitler in the movie "Er ist Wieder Da" (Look Who's Back) looms over a Pegida demonstration in November. Photo: DPA

The law hasn't stamped out racist and nativist thought or paranoid conspiracy theories about mainstream European politicians having a grand plan to replace the populations of their countries with Middle Eastern immigrants.

Plenty of people were more than willing to talk about such ideas on camera with a fake Hitler. And they form the backbone of the Pegida movement, which at its one-year anniversary heard a speaker only half-jokingly suggest that German officials would like to put their own people in concentration camps.

Instead, those ideas have been pushed underground and allowed to flourish in hermetic echo chambers, untouched by facts and counter-arguments from people and media outlets of a different political stripe.

The media bear special responsibility for their failure to respond to movements like Pegida with a positive message rather than mockery and condemnation, giving ammunition to those who dismiss all journalists and their work as part of the "Lügenpresse" (lying press).

Pegida founder Lutz Bachmann (l) shows off a shirt that reads "Lügenpresse" (lying press). Photo: DPA

As this strain of far-right thought becomes an increasing presence in European politics – with the AfD overtaking the Green and Left parties in Germany at one point last month, and France's Front National flirting with a credible candidacy at 2017's presidential elections – mainstream politicians need to think carefully about how they will fight it.

Will they do so by creating ever more martyrs – like anti-Semitic French comedian Dieudonné M'bala M'bala - to the cause of speaking the twisted "truth" that these movements peddle in the face of laughter and state repression by complacent incumbent parties?

Or will they find a way to fight these parties in the realm of facts, values and ideas, inoculating the public in their countries against men like Dieudonné or Pegida founder Lutz Bachmann?

If they take the first option, they should expect to see this new force continuing to ride high in the polls and attract new voters to its twisted thinking.

Taking the second option will require greater bravery – but in the long-term is the only way to uphold the values of tolerance, diversity and freedom of speech that our leaders praise so frequently.

Comments