How ordinary people smashed the Stasi

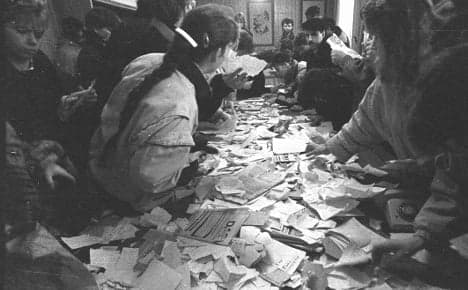

25 years ago today, just weeks after the fall of the Berlin Wall, hundreds of ordinary people stormed into Stasi offices in Erfurt to stop the repressive secret police destroying the records it kept on East Germans.

“We wanted to eliminate the apparatus of power and a just society of solidarity,” remembers 61-year-old Barbara Sengewald.

Civil rights activists like Sengewald and previously politically inactive ordinary people peacefully occupied the State Security (Stasi) local office in Erfurt, putting an end to the cloud of smoke from burning files which had hung in the air for days.

It was the first time ordinary citizens of the German Democratic Republic (GDR) had struck back against the secret police.

“We ordinary people didn't have any idea about secret services,” Sengewald said, “but we wanted to dissolve the secret service.”

For decades the Stasi had spied on their mail and phone conversations and suborned tens of thousands of ordinary people into informing on the political activities of their neighbours, friends and even families.

Their action inspired people all over the GDR to stop the destruction of the mountains of records on ordinary people kept by the Stasi.

On December 4th 1989, the fight back started when one transport worker blocked the entrance to the Erfurt Stasi office with his truck to stop any more of the shredded and burned documents being hauled away.

“There were so many who wanted to make a change and overcame their fear,” Sengewald said.

“There were old pensioners with the militia armands and young women with babies in their arms. They were worth just as much as those of us who had been campaigning for longer.

“It was a revolutionary time, unthinkable today.”

Every day brought fresh revelations on the Socialist Unity Party (SED) regime that had governed the GDR until its retirement on December 3rd.

“Be on the alert!” was the title of a leaflet printed by the New Forum, the umbrella group of activist organizations that had come together in the months leading up to the fall of the Wall.

Activists in Erfurt made 4,000 copies of the flyer and slipped it into their neighbours' postboxes on the night of December 3rd, hoping that enough of them would join them to make their blow against the Stasi hit home.

They had already tried petioning the mayor, the police and prosecutors to stop the destruction of the Stasi files.

“It wasn't that we trusted them, but we wanted to use them,” Sengewald said.

But the authorities weren't about to help citizens uncover the crimes of the hidden power which had kept them in fear for so long.

That left the non-violent occupation of the Stasi bureau as the only way for the citizens to find out just what the secret police had been up to in the shadows.

Today, Roland Jahn, Federal Commissioner for the Stasi Records and a former dissident who was expelled from the GDR, says that the Erfurt occupation was the signal for a unified wave of occupations across the country.

On the very same evening, offices in Suhl and Leipzig were occupied until the main Stasi headquarters in the Berlin district of Lichtenberg was occupied on January 15th.

“That's how people turned the peaceful protest movement into a peaceful revolution,” Jahn said.

For Jahn, the courageous women and men who carried out the occupations are the only reason that people can now search through the records about themselves which the Stasi had collected.

Researchers and the media have free access to the files, while new generations of Germans can be educated about the state surveillance which clamped a lid on popular resistance to the SED regime for so long.

Sengewald herself became leader of a group of citizen investigators who uncovered Stasi surveillance equipment in businesses and the post office.

Although the Stasi was the last bastion of power to fall and used the time it had to the full to try and cover up its activities, the civil rights activists “managed to set up pinpricks” to look back into their crimes, Sengewald said.

“We were able to show that courage and standing up for your convictions are worth it.”

SEE ALSO: The Local's Berlin Wall special

Comments

See Also

“We wanted to eliminate the apparatus of power and a just society of solidarity,” remembers 61-year-old Barbara Sengewald.

Civil rights activists like Sengewald and previously politically inactive ordinary people peacefully occupied the State Security (Stasi) local office in Erfurt, putting an end to the cloud of smoke from burning files which had hung in the air for days.

It was the first time ordinary citizens of the German Democratic Republic (GDR) had struck back against the secret police.

“We ordinary people didn't have any idea about secret services,” Sengewald said, “but we wanted to dissolve the secret service.”

For decades the Stasi had spied on their mail and phone conversations and suborned tens of thousands of ordinary people into informing on the political activities of their neighbours, friends and even families.

Their action inspired people all over the GDR to stop the destruction of the mountains of records on ordinary people kept by the Stasi.

On December 4th 1989, the fight back started when one transport worker blocked the entrance to the Erfurt Stasi office with his truck to stop any more of the shredded and burned documents being hauled away.

“There were so many who wanted to make a change and overcame their fear,” Sengewald said.

“There were old pensioners with the militia armands and young women with babies in their arms. They were worth just as much as those of us who had been campaigning for longer.

“It was a revolutionary time, unthinkable today.”

Every day brought fresh revelations on the Socialist Unity Party (SED) regime that had governed the GDR until its retirement on December 3rd.

“Be on the alert!” was the title of a leaflet printed by the New Forum, the umbrella group of activist organizations that had come together in the months leading up to the fall of the Wall.

Activists in Erfurt made 4,000 copies of the flyer and slipped it into their neighbours' postboxes on the night of December 3rd, hoping that enough of them would join them to make their blow against the Stasi hit home.

They had already tried petioning the mayor, the police and prosecutors to stop the destruction of the Stasi files.

“It wasn't that we trusted them, but we wanted to use them,” Sengewald said.

But the authorities weren't about to help citizens uncover the crimes of the hidden power which had kept them in fear for so long.

That left the non-violent occupation of the Stasi bureau as the only way for the citizens to find out just what the secret police had been up to in the shadows.

Today, Roland Jahn, Federal Commissioner for the Stasi Records and a former dissident who was expelled from the GDR, says that the Erfurt occupation was the signal for a unified wave of occupations across the country.

On the very same evening, offices in Suhl and Leipzig were occupied until the main Stasi headquarters in the Berlin district of Lichtenberg was occupied on January 15th.

“That's how people turned the peaceful protest movement into a peaceful revolution,” Jahn said.

For Jahn, the courageous women and men who carried out the occupations are the only reason that people can now search through the records about themselves which the Stasi had collected.

Researchers and the media have free access to the files, while new generations of Germans can be educated about the state surveillance which clamped a lid on popular resistance to the SED regime for so long.

Sengewald herself became leader of a group of citizen investigators who uncovered Stasi surveillance equipment in businesses and the post office.

Although the Stasi was the last bastion of power to fall and used the time it had to the full to try and cover up its activities, the civil rights activists “managed to set up pinpricks” to look back into their crimes, Sengewald said.

“We were able to show that courage and standing up for your convictions are worth it.”

SEE ALSO: The Local's Berlin Wall special

Join the conversation in our comments section below. Share your own views and experience and if you have a question or suggestion for our journalists then email us at [email protected].

Please keep comments civil, constructive and on topic – and make sure to read our terms of use before getting involved.

Please log in here to leave a comment.