Why is German-speaking Europe lagging on Covid vaccines?

From the legacy of Nazi policies to a widespread belief in alternative medicine, German-speaking Europe has made itself vulnerable to the emotion-laden appeals of the anti-vaccine movement.

Ahead of winter, much of German-speaking Europe has already been hit by a new set of measures, including stay-at-home orders, restaurant closures and compulsory vaccination orders.

In scenes reminiscent of late 2020, authorities are concerned about skyrocketing Covid case rates and rapidly dwindling hospital capacity.

A major reason for this is the region’s low vaccination rate, which trails other Western European countries.

German-speaking Europe’s low vaccination rate has drawn significant media attention, with a variety of explanations emerging, from poor initial vaccination messaging to the legacy of Nazi-era policies.

With approximately 100 million people living in German-speaking regions of the continent, reducing vaccine hesitancy to a few cultural touchstones may fail to tell the true story.

There are however a number of reasons why a reluctance to get vaccinated has taken hold in German-speaking parts of the continent.

German-speaking Europe at the back of the pack

On November 11th, journalist Wolfgang Blau tweeted the following graphic.

Warum? pic.twitter.com/9MwmMd4MFv

— Wolfgang Blau (@wblau) November 11, 2021

The graphic originally appeared in an article in Britain’s Financial Times discussing German-speaking Europe's comparatively poor vaccine take-up rate.

The report cited anti-establishment views and growing populism as the main reasons why German-speaking Europe is playing catchup on vaccines.

Two weeks on, the figures are relatively similar, with no country with a German-speaking majority managing to vaccinate more than 70 percent of their population.

The following graph shows that this sits below or equal to EU averages. Given that German is the most prevalent language spoken in the EU, it is perhaps no surprise that the EU average should be heavily influenced by that of German-speaking Europe.

The vaccine hesitancy is however not limited to countries with a German-speaking majority.

Even in the German-speaking northern Italian region of South Tyrol, around 29 percent of the 500,000-strong population is unvaccinated - giving it the lowest vaccination rate in all of Italy.

Switzerland, as a country where two thirds of the population speak German but with large French and Italian-speaking minorities, is perhaps the best country through which to analyse the phenomenon.

According to official Swiss data, of the seven cantons with a French-speaking majority or minority, six are above the Swiss average (67.05 percent of people with at least one shot), other than Jura, where the rate is 64.87 percent.

With 70.14 percent of the population with at least one jab, the Italian-speaking canton of Ticino is one of only three Swiss cantons to have crossed the 70 percent mark, alongside French-speaking Neuchâtel (Switzerland’s highest at 71.5 percent) and the urban, German-speaking canton of Basel City (70.47 percent).

French-speaking Switzerland: Seven life hacks that will make you feel like a local

While Switzerland’s vaccination rates are highest in urban centres and lowest in rural and regional cantons (more on that later), most of which are German-speaking, just six of the remaining 18 cantons - all of which are German-speaking - have a rate higher than the national average.

German-speaking Europe the new Covid epicentre

Partly as a consequence of the low vaccination rate German-speaking regions have become the new epicentre of Europe’s fourth Covid wave.

Germany reported an average of just under 50,000 cases per day over the past week, while Austria - which has just gone into nationwide lockdown has also hit a record number of new cases forcing it to become the first European country to announce compulsory Covid vaccinations.

Switzerland’s case rate is far lower, however that is at least in part due to the lack of widespread testing since October, when the government phased out free Covid tests.

For instance, on November 11th Austria tested more than 725,000 people, whereas Switzerland tested just 40,129.

Switzerland, where the Covid measures have consistently been some of the most relaxed in Europe, broke from its Germano-speaking neighbours by ruling out stricter measures last Thursday.

Experts however have suggested the government wants to avoid a protest vote in an upcoming referendum on the measures, set to take place this Sunday, which could jeopardise the country’s ability to respond to the pandemic.

READ MORE: Is Switzerland delaying imposing new measures due to Covid referendum?

Why German-speaking Europe is lagging on Covid vaccines

German-speaking Europe’s slow uptake on the vaccine front has surprised many, given the reputation of German-speaking countries as being calm, rational, practical and not prone to flights of conspiracy-induced fancy.

While German-speaking Europe does have a lower vaccination rate than that of the rest of western Europe, this alone doesn’t always tell the full story.

In Switzerland, the main factor in vaccination rates has more to do with the country’s regional versus urban divide than it does with the famous Röstigraben cultural and linguistic barriers in the country.

CHARTS: Which Swiss cantons have the highest vaccination rates?

The German-speaking metropolises of Zurich and Basel have vaccination rates well above the national average of 67.05 percent, while tiny French-speaking Jura’s one-jab rate of 64.87 percent resembles smaller, German-speaking rural cantons more than that in the French-speaking part of the country.

With larger cities feeling the brunt of the pandemic - both in terms of infection and fatality rates along with the economic impacts of lockdowns - experts argue that city dwellers are more likely to take the pandemic seriously.

One of the reasons for this urban-rural divide according to analysis conducted in June by Sotomo Institute in relation to Switzerland "is that there are more people hostile to the vaccine in rural areas. Perhaps simply in part because residents in the countryside have been less affected by the pandemic."

“Basically, cities are more willing to vaccinate. Rural cantons without urban centres are therefore noticeable because of their greater skepticism towards the corona vaccination”, study’s author Michael Hermann noted.

Austria's vaccine take up has also been marked by an urban-rural split, with rates much higher in the capital of Vienna than in much of the country's less populated areas.

Communities in the Inn and Mühlviertel, in parts of the Waldviertel, in Upper Carinthia, East Tyrol, in the Upper Inn Valley and in Flachgau and Tennengau have very low vaccination rates, which have not been helped by poorly informed chest-beating rhetoric aimed at turning country Austrians against their city counterparts.

The Mayor of Spiss - which throughout the pandemic has had Austria's lowest vaccination rate - Alois Jäger said in an interview with Puls24 that the low vaccination rate in the village was due to people being “more free’ in the country.

He also claimed the antibodies of residents of rural communities were better than those of people in the city because their children played in the mud, and said he had also not been vaccinated against Covid-19.

In Germany, while the urban and rural divide also plays out, cultural ties to eastern Europe also play a role.

Other than the urbanised city-state Berlin, the five German states with the lowest vaccination rates are the five former East German states of Saxony, Saxony Anhalt, Thuringia, Brandenburg and Mecklenburg Western-Pomerania.

READ MORE: Why are so many Germans reluctant to get vaccinated?

Studies have found those in the east have a lower trust in government, while the popularity of the populist, far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) - which contains many of Germany’s most prominent vaccine sceptics in government - is also far higher in the former east.

A study by Reimut Zohlnhöfer, a political scientist at Heidelberg University, showed a connection between far-right sentiment and a lack of willingness to get vaccinated, although vaccine scepticism can be seen across the political spectrum.

“We found a slight correlation with voting for the (far-right party) AfD," he said. "It seems that AfD voters seem to be less willing to get vaccinated."

Germany and Austria’s proximity to Eastern Europe also plays a role, with vaccine scepticism far higher in central and Eastern European states.

Although the following graph shows how Germany, Austria and Switzerland to be ahead of the pack when compared with a few eastern European countries.

Historical: Public health, protest and the legacy of National Socialism

Much of the coverage since the start of the pandemic has focused on the prevalence of anti-vaccination protests in German-speaking Europe.

While there is a link between vaccine scepticism and anti-establishment or populist politics, these are by no means limited to German-speaking Europe.

France in particular saw weekly protests against the country’s health pass, but France’s 77 percent vaccination rate (percentage of population who have had at least one dose) is seven percent higher than Germany’s - and ten percent higher than that of Switzerland.

One aspect which may explain this however is the degree to which populist sentiment in German-speaking countries has historically had health as a central element.

Heidelberg University's Zohlnhöfer believes that vaccine hesitancy has less to do with the vaccines themselves and more to do with a general trust, or lack thereof, in government and public institutions.

Unlike many Southern European countries, German-speaking Europe tends to have a higher focus on the individual on a societal basis, which flows into health policy and ultimately decision making.

Geneva epidemiologist Alessandro Diana pointed out that Switzerland “has invested a lot in the self-determination of its citizens”, the kind of freedom that encompasses the right to decide what to do (or not do) with one’s body.

Swiss Health Minister Alain Berset has frequently emphasised the individual focus of the vaccination campaign, rather than a message of protecting others.

"From the moment that everyone who wants to be vaccinated has been vaccinated, the goal is no longer to protect those who don't want to be vaccinated," Berset has said on multiple occasions.

However, given that everyone in Switzerland has now had access to free and easy vaccination for several months but so many don't appear likely to get the jab, it would appear that this message no longer rings true.

Thomas Steffen, cantonal doctor for Basel-Stadt, told Swiss news outlet Watson this was endemic in German-speaking health systems, which have long prioritised treating illnesses in individuals, rather than taking a broader approach grounded in public health, which would include a focus on prevention.

"Especially in Switzerland, medical perspectives that deal with the collective have been underdeveloped for decades," Steffen said. "We are world leaders when it comes to treating illnesses in individuals."

Steffen said health authorities must learn to adopt a collective rather than individual message in the future.

"Many medical problems can only be solved if we realise that we are not just eight million individuals in Switzerland."

Cultural: Cure rather than prevention

The reason the focus on individualistic approaches to health care are so embedded in the collective consciousness is at least in part due to the legacy of National Socialist (Nazi) health policies.

These sought to exact a greater degree of control over society through preventative aspects of health care - and in the aftermath of the Nazi era, in turn led to curative approaches becoming the contemporary preference.

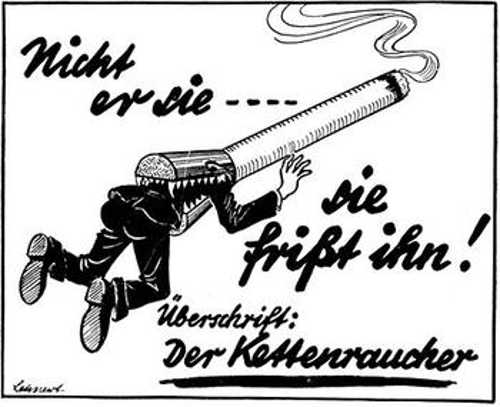

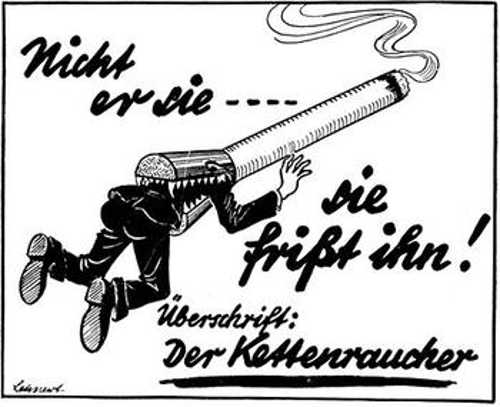

One Nazi policy sought to ban smoking as a preventative healthcare measure, with propaganda arguing it was an example of “the decadent fashion of political liberalism that is harmful to the race”.

A Nazi-era anti-smoking ad in German which reads "The chainsmoker: He doesn't consume it, it consumes him!" By The anti-tobacco campaign of the Nazis: a little known aspect of public health in Germany, 1933-45 - article published in the British Medical Journal, fair use,

Steffen told Watson that the harmful connotations meant that a proper public health discourse focusing on preventative care failed to develop in Germany, Austria and Switzerland, unlike in Latin and Anglo-Saxon parts of Europe.

"The DACH countries are 20, 30, maybe 40 years behind in the field of public health," Steffen said.

“(When compared to German-speaking Europe) Latin and Anglo-Saxon societies have never experienced such a trauma".

As a result, the use of the terms “public health” and “prevention” still hold a strong connection to Nazi-era policies.

Switzerland’s Watson news outlet points out that not one doctor in Germany has the title 'Prevention and Public Health' (Prävention und Public Health), whereas that title can be found among doctors in at least 40 other European countries.

A consequence of this is that the ultimate preventative medical treatment - vaccination, which effectively primes your body's own antibodies to fight off invaders - has been hampered by an emphasis on curative approaches.

Didier Pittet, head of the infection prevention service at Geneva’s University Hospitals, noted that Switzerland has never been a top performer when it comes to vaccination generally.

And “In Switzerland, many people are reluctant to vaccinate. We are, for example, the worst performers in Europe when it comes to measles vaccination”, Pittet added.

Education: Alternative medicine and Waldorf schools

German-speaking Europe’s tendency towards individualistic approaches to the pandemic also has its legacy in a strong, counter-cultural streak which emerged in the late 1960s, Swiss sociologist Oliver Nachtwey told Austria’s Der Standard broadsheet.

Wanting to distance themselves from the conformist working class of the 1950s and early 1960s, alternative approaches gained a foothold in German-speaking Europe which remain prevalent today.

“One wanted to stand out from the conformist mass workers of the 50s and 60s. They strived for a different way of life. They looked for authenticity, made a body-consciousness policy,” Nachtwey said.

“It was about esotericism and spiritualism. One has sent one's children to Waldorf schools, where the state education system is not obeyed. Alternative medicine was in trend.”

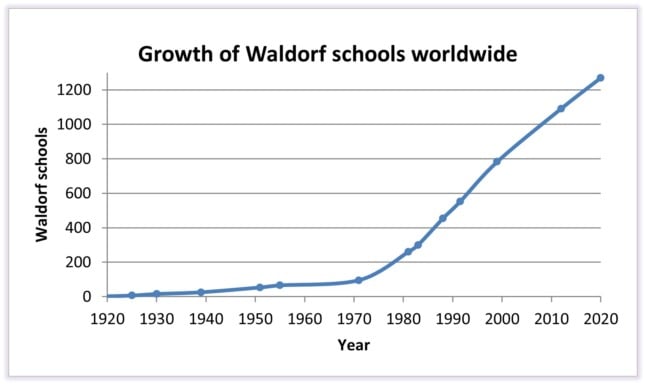

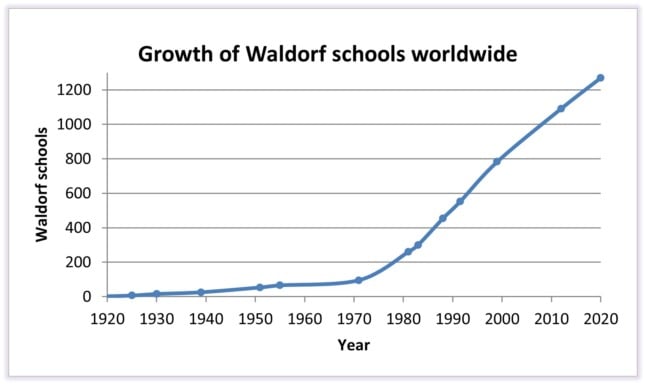

Waldorf schools, which preach the spiritual principles of ‘anthroposophy’, were shut down by the Nazis during the Second World War and in the eyes of some have remained symbolic of a bulwark against state overreach in German-speaking Europe.

There are 236 Waldorf schools in Germany, along with 32 in Switzerland and 21 in Austria.

Around a quarter of Germany’s Waldorf schools are in the wealthy south-western state of Baden-Württemberg, which has the lowest vaccination rate of any German state other than those of the former east.

“You can take a look at Baden-Württemberg. This is the hotspot of the lateral thinker (Querdenker) movement in Germany. At the same time there are more than 50 Waldorf schools there. So almost a quarter of all Waldorf schools in Germany. Many prominent lateral thinkers come precisely from this scene,” Nachtwey said.

READ MORE: How the spiritual 'Waldorf' movement is connected to German vaccine scepticism

While Waldorf schools do not reject science outright, their focus on spirituality and ‘thinking outside the box’ is a reason many are content to reject what they consider to be ‘mainstream medicine’.

"Many anthroposophists believe in the rule of karma, which is that illnesses can help atone for misdeeds in previous lives and bring about spiritual development," Spiegel journalist Tobias Rapp told AFP.

"That's why there are unfortunately in some Waldorf schools many sceptics with regards to vaccines. Some also subscribe to conspiracy theories," he said.

A graph showing the worldwide growth in Waldorf schools, which accelerated in the late 1960s and 1970s. Around a fifth of these are in Germany. By Clean Copy - Excel, CC BY-SA 4.0,

There is also a federation of doctors who subscribe to the anthroposophist philosophy. A network of anthroposophist clinics includes a hospital in Berlin which deploys ginger compresses and iron from meteorites as part of its medicinal toolbox on Covid patients.

"Meteorite iron is a medicine that we use in phase 2 of a Covid illness -- when the first symptoms of sickness are showing, we also use it in post-Covid syndrome --- when tiredness and weakness set in in the convalescence stage," said Harald Matthes, who heads the Havelhoehe hospital, in an interview with the daily Tagesspiegel.

Germany, despite being the home to influential pharmaceutical companies including BioNTech, the co-creator of one of the most popular Covid vaccines, retains a strong alternative medicine culture.

Political: Poor vaccination messaging and federalism

Another major factor which experts feel has hampered the vaccination campaigns has been a failure to adequately craft a message from health authorities that resonates with the general public.

Suzanne Suggs, professor at the University of Lugano, said authorities in German-speaking countries had sought to counter misinformation by adopting a facts-first approach in vaccine messaging, rather than seeking to appeal to people’s emotions.

A consequence of this however is that anti-vaccination groups were able to target poorly informed people with emotional messaging.

“It (the messaging) has been functional rather than emotional”, Suggs told the Financial Times.

“(This) led conspiracy theories to fill this void - they are often easier for the uninformed to believe.”

The federal structure of Germany, Switzerland and Austria has also placed more responsibility on states and cantons to administer vaccines and handle vaccination messaging, which has hampered the government’s chance of crafting a unified message to the people.

READ MORE: Why does Switzerland lag the EU in vaccinations?

Where to now for German-speaking Europe?

As at November 24th, Germany, Switzerland and Austria are walking relatively different paths when it comes to encouraging an uptick in vaccinations.

Austria's vaccine mandate will kick into effect on February 1st, while the nationwide lockdown - including a stay-at-home order - is due to end on December 12th but only for the vaccinated.

Switzerland, in deciding to maintain the status quo, has taken the opposite path, but with experts predicting Swiss hospitals are three weeks away from hitting Austria-like levels - and the Covid referendum just days away - they too might have their hands forced.

Germany has taken a middle of the road approach, last week reiterating it was the responsibility of the states to put in place appropriate measures. While Health Minister Jens Spahn this week said vaccine mandates "don't work", his hand too might be forced should Austria's harsh approach succeed in bringing an end to the pandemic.

Comments (1)

See Also

Ahead of winter, much of German-speaking Europe has already been hit by a new set of measures, including stay-at-home orders, restaurant closures and compulsory vaccination orders.

In scenes reminiscent of late 2020, authorities are concerned about skyrocketing Covid case rates and rapidly dwindling hospital capacity.

A major reason for this is the region’s low vaccination rate, which trails other Western European countries.

German-speaking Europe’s low vaccination rate has drawn significant media attention, with a variety of explanations emerging, from poor initial vaccination messaging to the legacy of Nazi-era policies.

With approximately 100 million people living in German-speaking regions of the continent, reducing vaccine hesitancy to a few cultural touchstones may fail to tell the true story.

There are however a number of reasons why a reluctance to get vaccinated has taken hold in German-speaking parts of the continent.

German-speaking Europe at the back of the pack

On November 11th, journalist Wolfgang Blau tweeted the following graphic.

Warum? pic.twitter.com/9MwmMd4MFv

— Wolfgang Blau (@wblau) November 11, 2021

The graphic originally appeared in an article in Britain’s Financial Times discussing German-speaking Europe's comparatively poor vaccine take-up rate.

The report cited anti-establishment views and growing populism as the main reasons why German-speaking Europe is playing catchup on vaccines.

Two weeks on, the figures are relatively similar, with no country with a German-speaking majority managing to vaccinate more than 70 percent of their population.

The following graph shows that this sits below or equal to EU averages. Given that German is the most prevalent language spoken in the EU, it is perhaps no surprise that the EU average should be heavily influenced by that of German-speaking Europe.

The vaccine hesitancy is however not limited to countries with a German-speaking majority.

Even in the German-speaking northern Italian region of South Tyrol, around 29 percent of the 500,000-strong population is unvaccinated - giving it the lowest vaccination rate in all of Italy.

Switzerland, as a country where two thirds of the population speak German but with large French and Italian-speaking minorities, is perhaps the best country through which to analyse the phenomenon.

According to official Swiss data, of the seven cantons with a French-speaking majority or minority, six are above the Swiss average (67.05 percent of people with at least one shot), other than Jura, where the rate is 64.87 percent.

With 70.14 percent of the population with at least one jab, the Italian-speaking canton of Ticino is one of only three Swiss cantons to have crossed the 70 percent mark, alongside French-speaking Neuchâtel (Switzerland’s highest at 71.5 percent) and the urban, German-speaking canton of Basel City (70.47 percent).

French-speaking Switzerland: Seven life hacks that will make you feel like a local

While Switzerland’s vaccination rates are highest in urban centres and lowest in rural and regional cantons (more on that later), most of which are German-speaking, just six of the remaining 18 cantons - all of which are German-speaking - have a rate higher than the national average.

German-speaking Europe the new Covid epicentre

Partly as a consequence of the low vaccination rate German-speaking regions have become the new epicentre of Europe’s fourth Covid wave.

Germany reported an average of just under 50,000 cases per day over the past week, while Austria - which has just gone into nationwide lockdown has also hit a record number of new cases forcing it to become the first European country to announce compulsory Covid vaccinations.

Switzerland’s case rate is far lower, however that is at least in part due to the lack of widespread testing since October, when the government phased out free Covid tests.

For instance, on November 11th Austria tested more than 725,000 people, whereas Switzerland tested just 40,129.

Switzerland, where the Covid measures have consistently been some of the most relaxed in Europe, broke from its Germano-speaking neighbours by ruling out stricter measures last Thursday.

Experts however have suggested the government wants to avoid a protest vote in an upcoming referendum on the measures, set to take place this Sunday, which could jeopardise the country’s ability to respond to the pandemic.

READ MORE: Is Switzerland delaying imposing new measures due to Covid referendum?

Why German-speaking Europe is lagging on Covid vaccines

German-speaking Europe’s slow uptake on the vaccine front has surprised many, given the reputation of German-speaking countries as being calm, rational, practical and not prone to flights of conspiracy-induced fancy.

While German-speaking Europe does have a lower vaccination rate than that of the rest of western Europe, this alone doesn’t always tell the full story.

In Switzerland, the main factor in vaccination rates has more to do with the country’s regional versus urban divide than it does with the famous Röstigraben cultural and linguistic barriers in the country.

CHARTS: Which Swiss cantons have the highest vaccination rates?

The German-speaking metropolises of Zurich and Basel have vaccination rates well above the national average of 67.05 percent, while tiny French-speaking Jura’s one-jab rate of 64.87 percent resembles smaller, German-speaking rural cantons more than that in the French-speaking part of the country.

With larger cities feeling the brunt of the pandemic - both in terms of infection and fatality rates along with the economic impacts of lockdowns - experts argue that city dwellers are more likely to take the pandemic seriously.

One of the reasons for this urban-rural divide according to analysis conducted in June by Sotomo Institute in relation to Switzerland "is that there are more people hostile to the vaccine in rural areas. Perhaps simply in part because residents in the countryside have been less affected by the pandemic."

“Basically, cities are more willing to vaccinate. Rural cantons without urban centres are therefore noticeable because of their greater skepticism towards the corona vaccination”, study’s author Michael Hermann noted.

Austria's vaccine take up has also been marked by an urban-rural split, with rates much higher in the capital of Vienna than in much of the country's less populated areas.

Communities in the Inn and Mühlviertel, in parts of the Waldviertel, in Upper Carinthia, East Tyrol, in the Upper Inn Valley and in Flachgau and Tennengau have very low vaccination rates, which have not been helped by poorly informed chest-beating rhetoric aimed at turning country Austrians against their city counterparts.

The Mayor of Spiss - which throughout the pandemic has had Austria's lowest vaccination rate - Alois Jäger said in an interview with Puls24 that the low vaccination rate in the village was due to people being “more free’ in the country.

He also claimed the antibodies of residents of rural communities were better than those of people in the city because their children played in the mud, and said he had also not been vaccinated against Covid-19.

In Germany, while the urban and rural divide also plays out, cultural ties to eastern Europe also play a role.

Other than the urbanised city-state Berlin, the five German states with the lowest vaccination rates are the five former East German states of Saxony, Saxony Anhalt, Thuringia, Brandenburg and Mecklenburg Western-Pomerania.

READ MORE: Why are so many Germans reluctant to get vaccinated?

Studies have found those in the east have a lower trust in government, while the popularity of the populist, far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) - which contains many of Germany’s most prominent vaccine sceptics in government - is also far higher in the former east.

A study by Reimut Zohlnhöfer, a political scientist at Heidelberg University, showed a connection between far-right sentiment and a lack of willingness to get vaccinated, although vaccine scepticism can be seen across the political spectrum.

“We found a slight correlation with voting for the (far-right party) AfD," he said. "It seems that AfD voters seem to be less willing to get vaccinated."

Germany and Austria’s proximity to Eastern Europe also plays a role, with vaccine scepticism far higher in central and Eastern European states.

Although the following graph shows how Germany, Austria and Switzerland to be ahead of the pack when compared with a few eastern European countries.

Historical: Public health, protest and the legacy of National Socialism

Much of the coverage since the start of the pandemic has focused on the prevalence of anti-vaccination protests in German-speaking Europe.

While there is a link between vaccine scepticism and anti-establishment or populist politics, these are by no means limited to German-speaking Europe.

France in particular saw weekly protests against the country’s health pass, but France’s 77 percent vaccination rate (percentage of population who have had at least one dose) is seven percent higher than Germany’s - and ten percent higher than that of Switzerland.

One aspect which may explain this however is the degree to which populist sentiment in German-speaking countries has historically had health as a central element.

Heidelberg University's Zohlnhöfer believes that vaccine hesitancy has less to do with the vaccines themselves and more to do with a general trust, or lack thereof, in government and public institutions.

Unlike many Southern European countries, German-speaking Europe tends to have a higher focus on the individual on a societal basis, which flows into health policy and ultimately decision making.

Geneva epidemiologist Alessandro Diana pointed out that Switzerland “has invested a lot in the self-determination of its citizens”, the kind of freedom that encompasses the right to decide what to do (or not do) with one’s body.

Swiss Health Minister Alain Berset has frequently emphasised the individual focus of the vaccination campaign, rather than a message of protecting others.

"From the moment that everyone who wants to be vaccinated has been vaccinated, the goal is no longer to protect those who don't want to be vaccinated," Berset has said on multiple occasions.

However, given that everyone in Switzerland has now had access to free and easy vaccination for several months but so many don't appear likely to get the jab, it would appear that this message no longer rings true.

Thomas Steffen, cantonal doctor for Basel-Stadt, told Swiss news outlet Watson this was endemic in German-speaking health systems, which have long prioritised treating illnesses in individuals, rather than taking a broader approach grounded in public health, which would include a focus on prevention.

"Especially in Switzerland, medical perspectives that deal with the collective have been underdeveloped for decades," Steffen said. "We are world leaders when it comes to treating illnesses in individuals."

Steffen said health authorities must learn to adopt a collective rather than individual message in the future.

"Many medical problems can only be solved if we realise that we are not just eight million individuals in Switzerland."

Cultural: Cure rather than prevention

The reason the focus on individualistic approaches to health care are so embedded in the collective consciousness is at least in part due to the legacy of National Socialist (Nazi) health policies.

These sought to exact a greater degree of control over society through preventative aspects of health care - and in the aftermath of the Nazi era, in turn led to curative approaches becoming the contemporary preference.

One Nazi policy sought to ban smoking as a preventative healthcare measure, with propaganda arguing it was an example of “the decadent fashion of political liberalism that is harmful to the race”.

Steffen told Watson that the harmful connotations meant that a proper public health discourse focusing on preventative care failed to develop in Germany, Austria and Switzerland, unlike in Latin and Anglo-Saxon parts of Europe.

"The DACH countries are 20, 30, maybe 40 years behind in the field of public health," Steffen said.

“(When compared to German-speaking Europe) Latin and Anglo-Saxon societies have never experienced such a trauma".

As a result, the use of the terms “public health” and “prevention” still hold a strong connection to Nazi-era policies.

Switzerland’s Watson news outlet points out that not one doctor in Germany has the title 'Prevention and Public Health' (Prävention und Public Health), whereas that title can be found among doctors in at least 40 other European countries.

A consequence of this is that the ultimate preventative medical treatment - vaccination, which effectively primes your body's own antibodies to fight off invaders - has been hampered by an emphasis on curative approaches.

Didier Pittet, head of the infection prevention service at Geneva’s University Hospitals, noted that Switzerland has never been a top performer when it comes to vaccination generally.

And “In Switzerland, many people are reluctant to vaccinate. We are, for example, the worst performers in Europe when it comes to measles vaccination”, Pittet added.

Education: Alternative medicine and Waldorf schools

German-speaking Europe’s tendency towards individualistic approaches to the pandemic also has its legacy in a strong, counter-cultural streak which emerged in the late 1960s, Swiss sociologist Oliver Nachtwey told Austria’s Der Standard broadsheet.

Wanting to distance themselves from the conformist working class of the 1950s and early 1960s, alternative approaches gained a foothold in German-speaking Europe which remain prevalent today.

“One wanted to stand out from the conformist mass workers of the 50s and 60s. They strived for a different way of life. They looked for authenticity, made a body-consciousness policy,” Nachtwey said.

“It was about esotericism and spiritualism. One has sent one's children to Waldorf schools, where the state education system is not obeyed. Alternative medicine was in trend.”

Waldorf schools, which preach the spiritual principles of ‘anthroposophy’, were shut down by the Nazis during the Second World War and in the eyes of some have remained symbolic of a bulwark against state overreach in German-speaking Europe.

There are 236 Waldorf schools in Germany, along with 32 in Switzerland and 21 in Austria.

Around a quarter of Germany’s Waldorf schools are in the wealthy south-western state of Baden-Württemberg, which has the lowest vaccination rate of any German state other than those of the former east.

“You can take a look at Baden-Württemberg. This is the hotspot of the lateral thinker (Querdenker) movement in Germany. At the same time there are more than 50 Waldorf schools there. So almost a quarter of all Waldorf schools in Germany. Many prominent lateral thinkers come precisely from this scene,” Nachtwey said.

READ MORE: How the spiritual 'Waldorf' movement is connected to German vaccine scepticism

While Waldorf schools do not reject science outright, their focus on spirituality and ‘thinking outside the box’ is a reason many are content to reject what they consider to be ‘mainstream medicine’.

"Many anthroposophists believe in the rule of karma, which is that illnesses can help atone for misdeeds in previous lives and bring about spiritual development," Spiegel journalist Tobias Rapp told AFP.

"That's why there are unfortunately in some Waldorf schools many sceptics with regards to vaccines. Some also subscribe to conspiracy theories," he said.

There is also a federation of doctors who subscribe to the anthroposophist philosophy. A network of anthroposophist clinics includes a hospital in Berlin which deploys ginger compresses and iron from meteorites as part of its medicinal toolbox on Covid patients.

"Meteorite iron is a medicine that we use in phase 2 of a Covid illness -- when the first symptoms of sickness are showing, we also use it in post-Covid syndrome --- when tiredness and weakness set in in the convalescence stage," said Harald Matthes, who heads the Havelhoehe hospital, in an interview with the daily Tagesspiegel.

Germany, despite being the home to influential pharmaceutical companies including BioNTech, the co-creator of one of the most popular Covid vaccines, retains a strong alternative medicine culture.

Political: Poor vaccination messaging and federalism

Another major factor which experts feel has hampered the vaccination campaigns has been a failure to adequately craft a message from health authorities that resonates with the general public.

Suzanne Suggs, professor at the University of Lugano, said authorities in German-speaking countries had sought to counter misinformation by adopting a facts-first approach in vaccine messaging, rather than seeking to appeal to people’s emotions.

A consequence of this however is that anti-vaccination groups were able to target poorly informed people with emotional messaging.

“It (the messaging) has been functional rather than emotional”, Suggs told the Financial Times.

“(This) led conspiracy theories to fill this void - they are often easier for the uninformed to believe.”

The federal structure of Germany, Switzerland and Austria has also placed more responsibility on states and cantons to administer vaccines and handle vaccination messaging, which has hampered the government’s chance of crafting a unified message to the people.

READ MORE: Why does Switzerland lag the EU in vaccinations?

Where to now for German-speaking Europe?

As at November 24th, Germany, Switzerland and Austria are walking relatively different paths when it comes to encouraging an uptick in vaccinations.

Austria's vaccine mandate will kick into effect on February 1st, while the nationwide lockdown - including a stay-at-home order - is due to end on December 12th but only for the vaccinated.

Switzerland, in deciding to maintain the status quo, has taken the opposite path, but with experts predicting Swiss hospitals are three weeks away from hitting Austria-like levels - and the Covid referendum just days away - they too might have their hands forced.

Germany has taken a middle of the road approach, last week reiterating it was the responsibility of the states to put in place appropriate measures. While Health Minister Jens Spahn this week said vaccine mandates "don't work", his hand too might be forced should Austria's harsh approach succeed in bringing an end to the pandemic.

Join the conversation in our comments section below. Share your own views and experience and if you have a question or suggestion for our journalists then email us at [email protected].

Please keep comments civil, constructive and on topic – and make sure to read our terms of use before getting involved.

Please log in here to leave a comment.