99 years since Rosa Luxemburg was murdered and dumped in a Berlin canal

Monday marks the 99th anniversary of the extra-judicial killing of the two most prominent German communists of the early twentieth century. But a memorial which took place on Sunday illustrates just how complicated their legacy is.

On January 15th 1919, paramilitaries burst into an apartment in western Berlin and seized the communist revolutionaries Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht. Although neither had an arrest warrant against them, they were both taken prisoner.

Luxemburg was tortured and killed and her body was dumped in the Landwehr Canal in Kreuzberg. Her corpse was only found months later. Liebknecht was taken to the Tiergarten park in the west of the city, where he was executed with a bullet in the head.

Within a matter of hours the two figureheads of revolutionary socialism in Germany had been extra-judicially murdered.

In the case of Luxemburg, who was 47 at the time, it can hardly be called a surprise that she died so young. Born in 1871 in Russian-controlled Poland, she was already involved in revolutionary politics when she was in high school and fled to Switzerland at the age of 18.

But she remained a member of the socialist intellectual circles, disagreeing with her Russian contemporaries on the importance of nationalism (she saw it as a bourgeois fascination). Just before the turn of the century, she moved to Berlin, where she became involved with the Social Democratic party (SPD). She always remained on the far-left of the party though, and when the SPD backed German involvement in the First World War, she went into opposition.

Liebknecht was six months Luxemburg’s junior. Born in Leipzig in 1871, he grew up in a left-wing household at a time when socialist parties were banned in Germany. Also highly educated, he studied law and political economy in Leipzig and then Berlin.

He forged a career as a lawyer and writer, spending time in jail for his text “militarism and anti-militarism.” While in jail, he still managed to win election into the Prussian Landtag, and in 1912 he was elected to the Reichstag.

Despite the fact that he was a parliamentarian, he was sent off to the eastern front to engage in non-combat duties. Tasked to peel potatoes, fell trees and bury the dead, Liebknecht suffered physical breakdown. He was kicked out of the SPD in 1916, an act that brought him into political union with Luxemburg.

Along with other revolutionaries the pair set up the anti-war Spartacus League in 1916. In their illegal communist underground, Liebknecht wrote and disseminated the revolutionary “Spartacus Letters”, calling for the overthrow of the government. Although the group's activities remained secret, both openly called for the end to the war and were imprisoned for their radical opinions.

In the revolutionary fervour that brought about the end of the war in 1918, the radicals were released from prison. At the very end of the year, they transformed the Spartacus league into the Communist Party of Germany.

In January, this new communist organization was quick to exploit the chaos that had swept Germany with defeat on the western front. They escalated demonstrations, with Liebknecht provocatively declaring on January 6th that the SPD government was no longer legitimate. by January 12th the protests had reached such a size that the government called in the army to quell them.

Liebknecht and Luxemburg went into the underground. But their days were numbered. After just three days paramilitaries from the conservative Freikorps found their hide out in the Wilmersdorf district of western Berlin. While the suspicion that the assassinations were carried out on orders from the SPD government has persisted, it has never been proved.

'Freedom to think differently'

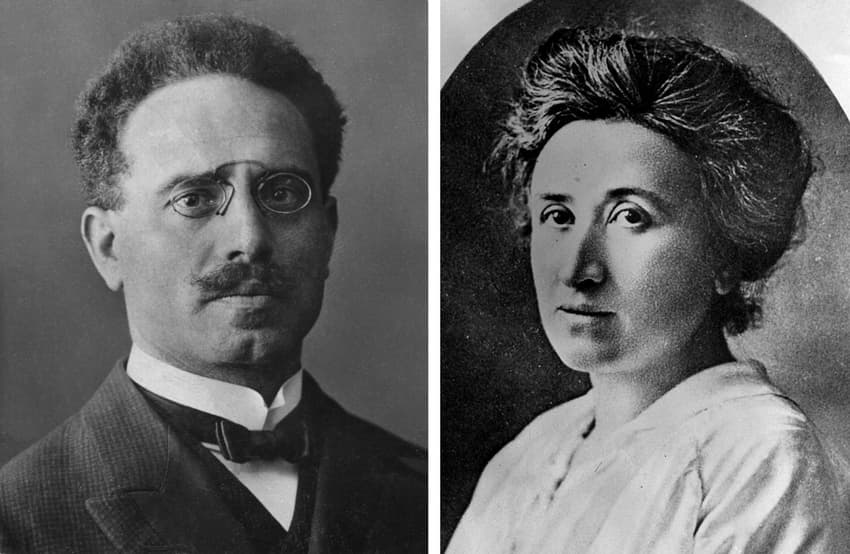

Photo: DPA

Photo: DPA

The communist revolutionaries of 1919 may be long gone, but they are far from forgotten. To this day, the deaths of Luxemburg and Liebknecht are remembered during an annual left-wing march in Berlin.

On Sunday, thousands of people turned out for the march organized by Die Linke (the Left Party) to the graveyard in eastern Berlin where the pair are buried.

The march, attended by Die Linke leaders such as Sahra Wagenknecht and Dietmar Bartsch, has been going on since the days of East Germany (GDR), when it was a key date in the calendar of the communist state.

But this year it did not just memorialize the 99th anniversary of the deaths of Luxemburg and Liebknecht, it also marked 30 years since a different but related crime.

In 1988 opponents of communist rule in East Germany turned up at the march carrying placards inscribed with famous quotes from Luxemburg. Most poignantly, one protester carried the famous quote “freedom is always freedom for those who think differently.”

Over the following days, more than a hundred people were arrested and threatened with severe prison sentences or even deported to West Germany.

In an age when Luxemburg has earned a reputation as a heroic female figure of early twentieth century history, Anna Kaminsky, head of the Federal Foundation for Understanding the GDR, warned of the oppressive legacy of her ideology.

“The history of communism can never be split from remembering those crimes and the injustice they involved,” Kaminsky said before the memorial.

Comments

See Also

On January 15th 1919, paramilitaries burst into an apartment in western Berlin and seized the communist revolutionaries Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht. Although neither had an arrest warrant against them, they were both taken prisoner.

Luxemburg was tortured and killed and her body was dumped in the Landwehr Canal in Kreuzberg. Her corpse was only found months later. Liebknecht was taken to the Tiergarten park in the west of the city, where he was executed with a bullet in the head.

Within a matter of hours the two figureheads of revolutionary socialism in Germany had been extra-judicially murdered.

In the case of Luxemburg, who was 47 at the time, it can hardly be called a surprise that she died so young. Born in 1871 in Russian-controlled Poland, she was already involved in revolutionary politics when she was in high school and fled to Switzerland at the age of 18.

But she remained a member of the socialist intellectual circles, disagreeing with her Russian contemporaries on the importance of nationalism (she saw it as a bourgeois fascination). Just before the turn of the century, she moved to Berlin, where she became involved with the Social Democratic party (SPD). She always remained on the far-left of the party though, and when the SPD backed German involvement in the First World War, she went into opposition.

Liebknecht was six months Luxemburg’s junior. Born in Leipzig in 1871, he grew up in a left-wing household at a time when socialist parties were banned in Germany. Also highly educated, he studied law and political economy in Leipzig and then Berlin.

He forged a career as a lawyer and writer, spending time in jail for his text “militarism and anti-militarism.” While in jail, he still managed to win election into the Prussian Landtag, and in 1912 he was elected to the Reichstag.

Despite the fact that he was a parliamentarian, he was sent off to the eastern front to engage in non-combat duties. Tasked to peel potatoes, fell trees and bury the dead, Liebknecht suffered physical breakdown. He was kicked out of the SPD in 1916, an act that brought him into political union with Luxemburg.

Along with other revolutionaries the pair set up the anti-war Spartacus League in 1916. In their illegal communist underground, Liebknecht wrote and disseminated the revolutionary “Spartacus Letters”, calling for the overthrow of the government. Although the group's activities remained secret, both openly called for the end to the war and were imprisoned for their radical opinions.

In the revolutionary fervour that brought about the end of the war in 1918, the radicals were released from prison. At the very end of the year, they transformed the Spartacus league into the Communist Party of Germany.

In January, this new communist organization was quick to exploit the chaos that had swept Germany with defeat on the western front. They escalated demonstrations, with Liebknecht provocatively declaring on January 6th that the SPD government was no longer legitimate. by January 12th the protests had reached such a size that the government called in the army to quell them.

Liebknecht and Luxemburg went into the underground. But their days were numbered. After just three days paramilitaries from the conservative Freikorps found their hide out in the Wilmersdorf district of western Berlin. While the suspicion that the assassinations were carried out on orders from the SPD government has persisted, it has never been proved.

'Freedom to think differently'

Photo: DPA

Photo: DPA

The communist revolutionaries of 1919 may be long gone, but they are far from forgotten. To this day, the deaths of Luxemburg and Liebknecht are remembered during an annual left-wing march in Berlin.

On Sunday, thousands of people turned out for the march organized by Die Linke (the Left Party) to the graveyard in eastern Berlin where the pair are buried.

The march, attended by Die Linke leaders such as Sahra Wagenknecht and Dietmar Bartsch, has been going on since the days of East Germany (GDR), when it was a key date in the calendar of the communist state.

But this year it did not just memorialize the 99th anniversary of the deaths of Luxemburg and Liebknecht, it also marked 30 years since a different but related crime.

In 1988 opponents of communist rule in East Germany turned up at the march carrying placards inscribed with famous quotes from Luxemburg. Most poignantly, one protester carried the famous quote “freedom is always freedom for those who think differently.”

Over the following days, more than a hundred people were arrested and threatened with severe prison sentences or even deported to West Germany.

In an age when Luxemburg has earned a reputation as a heroic female figure of early twentieth century history, Anna Kaminsky, head of the Federal Foundation for Understanding the GDR, warned of the oppressive legacy of her ideology.

“The history of communism can never be split from remembering those crimes and the injustice they involved,” Kaminsky said before the memorial.

Join the conversation in our comments section below. Share your own views and experience and if you have a question or suggestion for our journalists then email us at [email protected].

Please keep comments civil, constructive and on topic – and make sure to read our terms of use before getting involved.

Please log in here to leave a comment.