Berlin Wall? Ring the bell and come through

More than 150 kilometres of concrete, wire and guard towers ringed West Berlin from 1961 to 1989. But it’s not easy to carve up a city - and construction of the Wall threw up many freak instances.

On July 1st, 1988, around 200 West German environmentalists, punks and squatters used ladders to scale the Berlin Wall at Potsdamer Platz and entered East Germany (the GDR).

The communist authorities responded not by opening fire but by serving them breakfast and sending them home on the train. The Lenné Triangle, a four-hectare plot of East German territory located inside West Berlin, had been occupied since March in protest at developers’ plans for the area.

Despite clashes with water cannons and tear gas, West German police were powerless to clear the site, while GDR authorities stood back and watched.

“We made a mockery of the [West Berlin] Senate,” Stephan Noé, the protest leader and unofficial mayor of the encampment, said years later. “Imagine, 200 people who don’t give two hoots what any official dogsbody had to say.”

The countries finally agreed to exchange this and other pockets of land located on the wrong side of the Wall.

Once the deal was inked, West German police moved in to evict the squatters, who surprised everybody by crossing into the East German ‘death strip’ security zone.

The triangle was one of many oddities that magnified the folly of partitioning an entire city.

“The Wall circled Berlin like a noose, looping through the countryside beyond the western suburbs then running through the city following exactly the extent of the Soviet sector there,” British journalist and author Christopher Hilton wrote in his book ‘After the Berlin Wall’.

“That’s why it zigged and zagged. Inevitably it created anomalies and absurdities amidst the human misery of sudden separation.”

High security weekend

In Spandau, in the far west of the British sector, the tiny allotment community of Erlengrund was a West German enclave located in GDR territory.

“The owners had to pass through the death strip to reach their plots – and for that there was an iron door in the Wall with a doorbell,” Dr Hans-Hermann Hertle of the Potsdam Centre for Research into Contemporary History told The Local.

One man with extensive access to the border recalls the doorbell set-up very well.

Hendrik Pastor, a French photographer who worked for the western allies in Berlin in the 1980s, observed from the ground and air how life here unfolded.

West German owners used to ring at the door and pass to a control booth in the death strip to show their documents. Then they exited the other side and spent the weekend in isolation, hemmed in by wall, fencing and East German boats patrolling the adjacent lake.

Eventually the doorbell entrance was removed and a large automatic gate installed, “because residents wanted to bring furniture to their houses that wouldn’t fit through the door,” said Pastor, who spent 15 years documenting the Wall and its features.

There were plus sides, though: “They were safe. There were no burglaries.”

There were also remote spots where the two lines of wall or fencing were so close that a person could have leapt across – had they known.

But the fear of booby traps, the presence of security officials’ houses in these areas, and a pervasive fear of the border in general kept people away.

Chopper ride to school

In Steinstücken, a part of West Berlin in the Babelsberg district of Potsdam in the GDR, the 1961 erection of the Wall cut off a cluster of ten houses from the western ‘mainland’.

US helicopters had to fly in supplies for the residents and ferry the children to school until a one-kilometre road was built to the hamlet, sandwiched by concrete panels and towers.

As for the number of vulnerable points on the Wall where fewer installations and guards made an easy escape feasible, Pastor smiles: “How about a thousand?”

Mind the gap

While roads could be closed off and traffic redirected, the city’s overground and underground railway systems were harder to split, producing another quirk of partition.

Because the S-Bahn urban railway had always been operated by the Reichsbahn, which was now controlled by the GDR, trains running through the west of the city were still owned by East Berlin.

The staff were West Berliners but wore East German uniforms and were paid by the GDR in western deutschmarks, the proceeds going to the Reichsbahn.

The counterpoint of this was that some U-Bahn underground lines started and finished in West Berlin.

Stations in the East were bricked up and western-run trains had to pass slowly through tunnels that were lined with spike racks to stop people from trying to stow away.

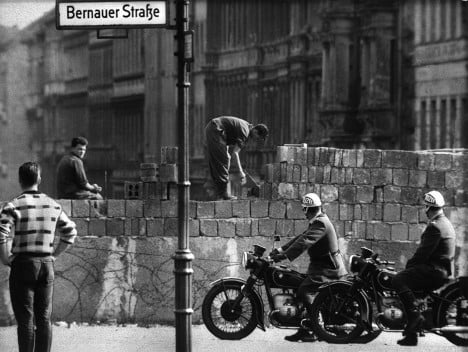

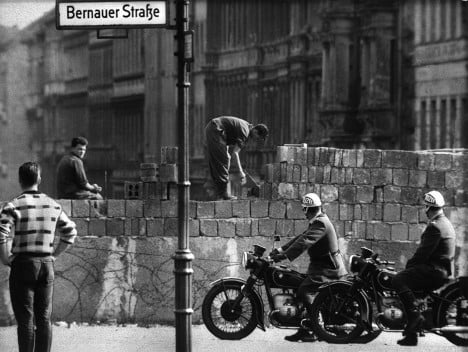

At Bernauer Street in the city centre, abrupt partition in 1961 put the U-Bahn entrance in West Berlin and the platforms in the East.

Above ground, the walls of the houses formed the border, prompting people to climb or leap to the West from their windows. At least one person died in this way.

The houses were later demolished to make way for larger security installations and a wide death strip. One of the longest preserved sections of the Berlin Wall can be seen here.

'There’s just – nothing'

The physical barrier was not the actual frontier, however. East German territory usually extended a few or even hundreds of metres in front so that personnel could exit small iron doors in emergencies or to do maintenance, including repainting graffiti-daubed sections.

But if the Wall presented a vivid, multi-coloured spectacle from the Western side, the other was a drab testament to its function. It was a largely insurmountable barrier, forbidding and faceless, apart from the peering heads of sentries.

“When I first saw the wall in East Berlin I’m not sure what I was expecting but it was a bit like seeing the stump of an amputated limb,” commented a former US resident of the city. “You might think in advance that it will look horrible, but actually there's just - nothing.”

After November 9th, 1989, Wall stretches in places like Steinstücken were among the first to be ripped down by locals.

Do you have memories of the Wall to share? Email [email protected]

By Nick Allen

Comments

See Also

On July 1st, 1988, around 200 West German environmentalists, punks and squatters used ladders to scale the Berlin Wall at Potsdamer Platz and entered East Germany (the GDR).

The communist authorities responded not by opening fire but by serving them breakfast and sending them home on the train. The Lenné Triangle, a four-hectare plot of East German territory located inside West Berlin, had been occupied since March in protest at developers’ plans for the area.

Despite clashes with water cannons and tear gas, West German police were powerless to clear the site, while GDR authorities stood back and watched.

“We made a mockery of the [West Berlin] Senate,” Stephan Noé, the protest leader and unofficial mayor of the encampment, said years later. “Imagine, 200 people who don’t give two hoots what any official dogsbody had to say.”

The countries finally agreed to exchange this and other pockets of land located on the wrong side of the Wall.

Once the deal was inked, West German police moved in to evict the squatters, who surprised everybody by crossing into the East German ‘death strip’ security zone.

The triangle was one of many oddities that magnified the folly of partitioning an entire city.

“The Wall circled Berlin like a noose, looping through the countryside beyond the western suburbs then running through the city following exactly the extent of the Soviet sector there,” British journalist and author Christopher Hilton wrote in his book ‘After the Berlin Wall’.

“That’s why it zigged and zagged. Inevitably it created anomalies and absurdities amidst the human misery of sudden separation.”

High security weekend

In Spandau, in the far west of the British sector, the tiny allotment community of Erlengrund was a West German enclave located in GDR territory.

“The owners had to pass through the death strip to reach their plots – and for that there was an iron door in the Wall with a doorbell,” Dr Hans-Hermann Hertle of the Potsdam Centre for Research into Contemporary History told The Local.

One man with extensive access to the border recalls the doorbell set-up very well.

Hendrik Pastor, a French photographer who worked for the western allies in Berlin in the 1980s, observed from the ground and air how life here unfolded.

West German owners used to ring at the door and pass to a control booth in the death strip to show their documents. Then they exited the other side and spent the weekend in isolation, hemmed in by wall, fencing and East German boats patrolling the adjacent lake.

Eventually the doorbell entrance was removed and a large automatic gate installed, “because residents wanted to bring furniture to their houses that wouldn’t fit through the door,” said Pastor, who spent 15 years documenting the Wall and its features.

There were plus sides, though: “They were safe. There were no burglaries.”

There were also remote spots where the two lines of wall or fencing were so close that a person could have leapt across – had they known.

But the fear of booby traps, the presence of security officials’ houses in these areas, and a pervasive fear of the border in general kept people away.

Chopper ride to school

In Steinstücken, a part of West Berlin in the Babelsberg district of Potsdam in the GDR, the 1961 erection of the Wall cut off a cluster of ten houses from the western ‘mainland’.

US helicopters had to fly in supplies for the residents and ferry the children to school until a one-kilometre road was built to the hamlet, sandwiched by concrete panels and towers.

As for the number of vulnerable points on the Wall where fewer installations and guards made an easy escape feasible, Pastor smiles: “How about a thousand?”

Mind the gap

While roads could be closed off and traffic redirected, the city’s overground and underground railway systems were harder to split, producing another quirk of partition.

Because the S-Bahn urban railway had always been operated by the Reichsbahn, which was now controlled by the GDR, trains running through the west of the city were still owned by East Berlin.

The staff were West Berliners but wore East German uniforms and were paid by the GDR in western deutschmarks, the proceeds going to the Reichsbahn.

The counterpoint of this was that some U-Bahn underground lines started and finished in West Berlin.

Stations in the East were bricked up and western-run trains had to pass slowly through tunnels that were lined with spike racks to stop people from trying to stow away.

At Bernauer Street in the city centre, abrupt partition in 1961 put the U-Bahn entrance in West Berlin and the platforms in the East.

Above ground, the walls of the houses formed the border, prompting people to climb or leap to the West from their windows. At least one person died in this way.

The houses were later demolished to make way for larger security installations and a wide death strip. One of the longest preserved sections of the Berlin Wall can be seen here.

'There’s just – nothing'

The physical barrier was not the actual frontier, however. East German territory usually extended a few or even hundreds of metres in front so that personnel could exit small iron doors in emergencies or to do maintenance, including repainting graffiti-daubed sections.

But if the Wall presented a vivid, multi-coloured spectacle from the Western side, the other was a drab testament to its function. It was a largely insurmountable barrier, forbidding and faceless, apart from the peering heads of sentries.

“When I first saw the wall in East Berlin I’m not sure what I was expecting but it was a bit like seeing the stump of an amputated limb,” commented a former US resident of the city. “You might think in advance that it will look horrible, but actually there's just - nothing.”

After November 9th, 1989, Wall stretches in places like Steinstücken were among the first to be ripped down by locals.

Do you have memories of the Wall to share? Email [email protected]

By Nick Allen

Join the conversation in our comments section below. Share your own views and experience and if you have a question or suggestion for our journalists then email us at [email protected].

Please keep comments civil, constructive and on topic – and make sure to read our terms of use before getting involved.

Please log in here to leave a comment.